Last month the US Treasury placed sanctions on cryptocurrency mixer Tornado cash causing a considerable amount of pushback and questions about the suitability and legality of sanctions on Tornado cash. The sanctions on Tornado cash follow an increasing amount of sanctions levied by the US Treasury in the cryptocurrency space, including those against Suex, Garantex, and Blender.io.

A natural question that has arisen is whether such sanctions are an effective way of combating cybercrime and money laundering. If so, are they reasonable and practical, given the legal and privacy concerns voiced by those with dissenting opinions?

Sanctions: A Tool Increasing Being Used by Government in the Cryptocurrency Space

The usage of sanctions involving cryptocurrency addresses and actors is not a particularly new development. The US government has often introduced sanctions focused on cryptocurrency activity against certain individuals, including those involved in terrorism, fringe groups, such as those involved in terrorism, and nation-state actors like North Korea’s Lazarus Group, as but a few examples.

In 2021, a crackdown of sorts started, with the US Treasury enacting sanctions on a wider range of entities. This includes select cryptocurrency exchanges, OTCs, and Nested Services including Suex, Chatex, and Garantex. But not because these exchanges were directly responsible for ransomware attacks. Rather, because they were allegedly facilitating and knowingly involved in money laundering for various ransomware actors, and in the latter case, laundering money from Hydra market, a darknet market shut down earlier this year.

In May 2022, for the first time ever, the US government introduced sanctions against a cryptocurrency mixer, namely Blender.io, which is a centralized and custodial Bitcoin mixing service. This was because of the use of Blender.io in a high amount of illicit activity, and in particular because the DPRK and state-sponsored Lazarus group used it to launder illicit proceeds of their ill-gotten gains. However, the US Treasury notes that Blender.io has also consistently been utilized by ransomware actors to launder ill-gotten proceeds as well.

This has drawn some criticism from certain Bitcoin privacy advocates (most of which have a poor understanding of blockchain forensics), claiming that it’s an overreach and/or that such actions constitute the US government trying to prohibit and/or invade individual privacy. We’ll dig into such assertions in more detail later in this blog post.

In August 2022, the US Treasury imposed sanctions on Tornado Cash and indicated a core reason for doing so was its usage in various cryptocurrency thefts perpetrated by Lazarus group, whereby hundreds of millions of dollars of cryptocurrency was laundered through Tornado Cash.

Arguments Against Sanctions on Tornado Cash

In our opinion, the arguments against sanctioning Tornado cash can be broken down into five main areas, and three of these could be equally applied to Blender.io, but the remaining two cannot be.

Assault on Privacy Argument: The Right to Anonymity and Privacy

A common argument put forward is that users have an inherent right to privacy and anonymity. And it’s argued that the actions taken to Sanction Tornado cash allegedly amount to an assault on that privacy and an effort to prevent anonymity. Thus, it is argued that sanctioning Tornado cash violates the fundamental human right to privacy.

The Argument That Some Innocent Individuals Will Be Wrongly Targeted

Obviously, not all individuals that have used Tornado cash (or other mixers for that matter) have done so for nefarious reasons, and there are completely legitimate reasons why a user may sometimes want to use such a service anyway.

However, Tornado Cash sanctions will inevitably lead to some individuals being targeted or affected by the sanctions when they didn’t do anything wrong. This could allegedly include account(s) being frozen because of a nexus to Tornado cash and/or an investigation into a user’s activities.

The Decentralization of Tornado Cash, Smart Contracts, and OFAC’s Alleged Lack of Mandate

This is a core argument put forward that one cannot put forward with an entity like Blender.io. Since Tornado cash does not take custody over users’ funds at any point and because Tornado cash can be described as self-executing code from various smart contracts running on multiple public blockchains, and the operation of those these contracts cannot be altered or stopped by anyone, including the Tornado Cash DAO, it’s argued that it’s not within OFAC’s mandate to sanction.

Thus, because Tornado cash is essentially self-executing code, a legal argument has been put forward claiming that Tornado cash does not constitute a ‘legal person’ that can be subject to sanctions, and thus OFAC is allegedly overstepping its authority granted to them by US congress. This is the substance of the lawsuit against the US treasury that Coinbase is supporting.

So the difference between Blender.io and Tornado cash is such that in the case of Tornado cash simply self-executing code, and to which no ‘legal person’ is responsible for operating, thus suggesting that sanctions against such an entity are not within OFAC’s mandate.

Additionally, it is argued that trying to sanction code could set a dangerous precedent regarding privacy.

The ‘Free Speech’ Argument and “You Can’t Sanction Code”

It’s also alleged in the Coinbase-supported lawsuit against the Treasury that the decision of users regarding the ability to choose whether or not to utilize Tornado cash is a ‘free speech’ issue, and sanctioning Tornado cash allegedly violates users’ free speech rights under the First Amendment in the United States.

The reasoning put forward for this dates back to the 1996 landmark case Bernstein v. Department of Justice, which established that computer code should be considered speech.

Blanket Sanctions Unreasonable Just because of Some Unwanted Uses Argument

Another argument is that it is unreasonable to prohibit and/or ban the use of a technology or service just because it is sometimes used for illicit purposes. One common analogy that is often made here is to (physical) cash, such as due to its use in illicit activity (e.g., narcotics) and the challenges associated with trying to trace cash.

Assessment of Tornado Cash Sanctions

In response to the arguments put forward which oppose sanctions against Tornado Cash, we have provided some insight on them and in some cases, counterarguments below:

The Assault on Privacy Counterargument

There are a lot of misconceptions amongst cryptocurrency users about how blockchain forensics and transaction monitoring would supposedly be an assault on individual privacy. Much of these beliefs stem from an inherently poor understanding of blockchain forensics and a general mistrust of government (a common theme among cryptocurrency enthusiasts).

Some privacy enthusiasts like to suggest that sanctioning Tornado cash amounts to efforts to have thorough surveillance over the Ethereum blockchain in some sort of 1984-esque manner.

The reality is that these individuals have a plethora of misconceptions about just what can be determined from on-chain data, and assertions over the level of surveillance have no basis in reality.

A cryptocurrency wallet is already anonymous when it is set up by an individual. The individual does not need to seek permission from anyone in order to set it up. Ultimately, only the owner of a wallet knows for certain when and if they own a given wallet unless they’ve elected to disclose that ownership to someone else (e.g., on Twitter, by providing a digital signature, etc.)

There are occasions when ownership of certain wallets can be determined with varying degrees of certainty with the help of on-chain data, in conjunction with account records which may include personal information (such as a name if it’s a KYC’d exchange account). For example, a forensic investigation analyst might observe that the owner of Coinbase Account A sent 2 Bitcoin to Wallet B, which then sent it back to the same Coinbase Account A.

This could potentially allow the analyst to conclude that Wallet B might belong to the same individual that controls Coinbase Account A, although there would often still be a degree of uncertainty. However, even if a very simple and straightforward case like the one described above, there are situations where the owner of Wallet B would not be the same as the owner of Coinbase Account A.

Even still, to obtain such personal information in the first place, one would need data from the applicable exchange or service (in this case, it’s a KYC’d service, but many services don’t require or utilize KYC). A blockchain analysis firm (like Cryptoforensic Investigators, Chainalysis, etc..) isn’t going to have access to such personal data, as exchanges don’t just hand out personal data to companies that ask. Getting such data requires an official inquiry to the service by law enforcement, a subpoena or court order, or sometimes both. Thus your personal information held by the applicable exchange is well-protected, albeit obtainable in certain circumstances through appropriate due process.

Another thing is that some individuals seem to get the idea that the names of wallet owners or suspected wallet owners are being recorded in a database by analytics companies and then sold. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Analytics software does not contain personal information (e.g., names, emails, etc)

Finally, some people get the idea that the government is carefully trying to monitor and/or surveil all the wallets on the blockchain or surveilling many of the transactions on the blockchain. Such an assertion is also completely off-base. Government agencies don’t have anywhere near enough resources to do that, even if they wanted to. Government agencies do sometimes investigate select specific activity or transactions that they find to be suspicious, but this activity constitutes a minuscule sliver of activity compared to the amount of transaction volume happening on applicable blockchains overall.

So if you think your government is watching or trying to uncover your transactions, or a blockchain analytics company is taking the time to uncover your activity for the sake of it, you’re almost certainly giving yourself far too much credit; you’re not important, and generally speaking, no one cares about the transactions you do.

Thus the ‘Assault on Privacy’ argument amounts to little more than a scare tactic perpetuated by those with extremely minimal understanding of how transactions are tracked and how and when personal data can be gathered based on such transaction data that could potentially lead to deanonymization.

Innocent Individuals Being Wrongly Targeted

It is conceivable that there may be some cases whereby individuals may be subject to increased scrutiny or may otherwise face accusations as a result of sanctions on Tornado cash in some cases. This is because certain wallet owners will seem to have done business with a high-risk entity that has often been utilized for money laundering.

While we think these incidents will be few and far between, some might argue that some level of increased due diligence is justifiable given the high amount of illicit activity involving Tornado cash which should be readily apparent to anyone that has used it. And thus, just as an individual that runs in the same circles as those involved in narcotics trafficking, underground gambling, or money laundering might at some point find themselves under scrutiny as well, a similar argument could be made about individuals that have a significant amount of Tornado Cash usage – it may be reasonable to suggest increased due diligence on select individuals.

This is precisely why it generally doesn’t make sense for most people with licit funds to use a service like Tornado Cash. The goal such users have is to generally ‘enhance’ their privacy (under the notion that someone is watching them and knows their personal information, which, as we previously discussed, is typically bollocks) and so to help ensure their activity isn’t scrutinized.

But the reality is that using a service like Tornado cash would end up significantly increasing the likelihood of a user having their activity come under scrutiny since Tornado Cash, even pre-Sanction would be regarded as a very high-risk service from a compliance standpoint. A Tornado cash connection, especially in large amounts would in the vast majority of cases subject a user with licit funds to much more scrutiny, not less.

Fortunately, in the rare situations where an individual may come under scrutiny as a result of Tornado Cash activity, there’s an easy solution that would enable them to absolve themselves of wrongdoing. It’s called a ‘Source of Wealth’ inquiry.

If the funds a user receive derive from Tornado cash receipts that they received into a wallet of theirs, then it’s as simple as providing the Tornado cash compliance reports or compliance notes, and in some cases a brief explanation or additional documentation detailing how such funds were obtained (e.g. earnings from trading, from an initial investment made, business income, etc.)

Interestingly, this is precisely what happened in a recent case that we’ve worked on where we were was hired by the Defendant’s counsel whereby the Defendant was (wrongly) accused (by the Plaintiff) of receiving millions of dollars in a hack/theft via Tornado cash, and such allegations turned out to be provably false (to the dismay of both the Plaintiff, their counsel, and their ‘expert’ who accused him).

Thoughts on the OFACs mandate and the Decentralization of Tornado Cash

This argument put forward is undoubtedly a legal argument in this regard, not a technical one, and the argument relates to the mandate that OFAC has (or doesn’t have). At Cryptoforensic Investigators, we aren’t lawyers and don’t provide legal opinions. But we can provide some pertinent technical insight related to this.

Two key areas that OFAC is mandated to target and regularly targets with sanctions include those related to National Security (and ransomware is undoubtedly a national security concern), and actors involved in the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction, which Lazarus group is involved in since the ‘revenue’ they generate goes toward nuclear weapons development and propping up the North Korean government developing them.

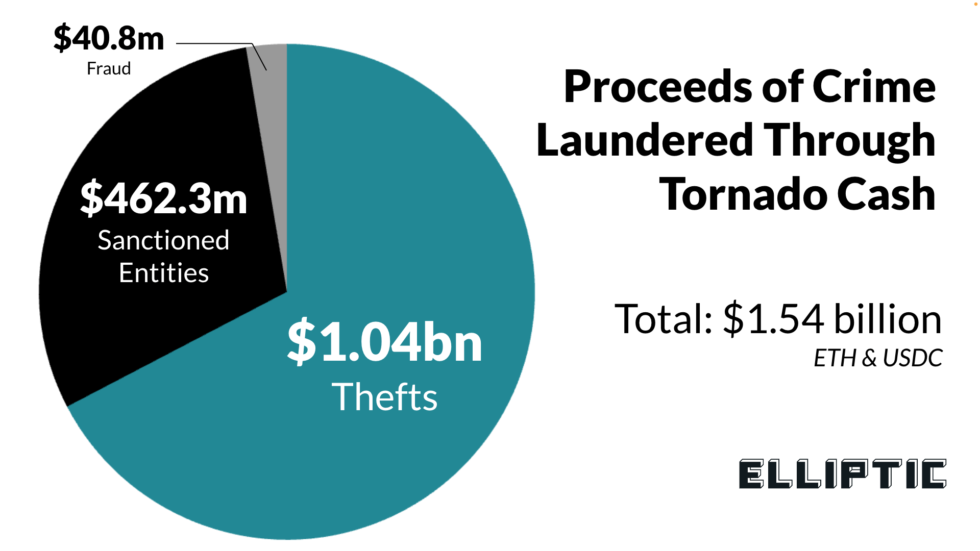

A key thing that may play a role in any legal decision is how often Tornado Cash is sometimes used for money laundering. Is only a small fraction of Tornado Cash activity illicit? Or a majority? According to Elliptic, over $7 billion USD of cryptoassets have been sent through Tornado cash (ETH & USDC only), and of that $462.3 million is attributable to sanctioned entities, and $1.54 billion is attributable to proceeds of crime once other thefts and frauds are factored in as well. This means at least 22% of Tornado cash activity is attributable to the proceeds of a crime.

Source: Elliptic

While the $7 billion figure is roughly accurate, there are a few critically important reasons that would suggest the $1.54 billion figure and $462.3 million figures are likely to be massive understatements.

- The figures are based on known/attributed thefts and do not factor in non-attributed thefts. There are many thefts that are not publicly reported and which even forensics companies don’t have attribution data on (or they only have data on a relatively small portion of them). Additionally, the $462.3 million figure associated with Sanctioned Entities (primarily Lazarus group) is based on a few select cases that Elliptic knows are attributable to such entities and does not incorporate other Lazarus group hacks that they don’t know about or which haven’t been attributed to Lazarus group.

- The figures do not factor in funds that have been sent to a service or exchange prior to being sent to Tornado cash. For example, if stolen funds are first sent to an exchange like OKX before being withdrawn, they would not be factored into such calculations. Additionally, if there was a large amount of another cryptocurrency asset stolen that was converted to ETH/USDC via coinswapping services first before going to Tornado cash, that also wouldn’t be factored into such calculations since those funds would have the appearance of coming from that service, and not the theft per se.

- There are also cases where people send funds to Tornado cash, only then to send it back into Tornado cash a second time. Because of the way the figures are calculated, the 2nd time it goes into Tornado cash, Elliptic would be counting the funds as licit, not illicit, as they wouldn’t inherently have the appearance of being attributable to the same theft as the initial Tornado cash deposits were, as the source of funds going into Tornado cash during the second series of deposits would be… Tornado cash! In our opinion, it would still be unfair to count the second time they go into Tornado cash as licit.

It is for these reasons that at Cryptoforensic Investigators, we think the 22% figure is a gross underestimate. Once we factor in these considerations and what we know about the illicit activity that happens through Tornado cash in our own cases, we think it’s likely the amount of illicit activity involving Tornado cash is probably in excess of 50%, although there admittedly is no explicit way to confirm this figure. The only figures that can be safely confirmed as a lower threshold would be the figures provided by Elliptic.

This begs the question: if such a large portion of activity involving Tornado Cash is illicit in nature, could that change how Tornado cash ought to be treated from a legal perspective?

Another factor to keep in mind is that there is that unless Tornado cash can be ‘traced through’ (which can be possible in select cases to varying degrees of certainty or uncertainty which vary depending on the case), there is no effective legal recourse that law enforcement would have since unlike an exchange service, Tornado cash cannot be subpoenaed for information and doesn’t have the information law enforcement would seek anyway. Indeed that’s one of the main purposes of Tornado cash – by severing the on-chain link, users are trying to expressly prevent any such recourse, regardless of who is attempting to do so, or the reasons for doing so.

This also begs the question: Given the lack of legal recourse available when Tornado cash is involved, could that change how Tornado cash ought to be treated from a legal perspective?

Also, here’s another little interesting thought exercise worth considering:

What if instead of sanctioning Tornado cash, every address that interacted with Tornado cash that can be deemed to belong to a ‘legal person’ (i.e., not belonging to self-executing code or a smart contract) were to be sanctioned instead? Would this then be within OFACs mandate? Would this be considered overreach?

Thoughts on the “You Can’t Sanction Code” Argument

This is yet another legal argument, which we’ll will avoid expressing a legal opinion on, but can provide some technical insight.

For starters, the US Treasury has clarified that residents who elect to copy and/or re-publish Tornado Cash’s open-source code would not be violating sanctions by doing so. Thus, it doesn’t seem like the code or the reproduction of it is being sanctioned. Rather code/technology in the way that it’s been currently implemented under the moniker ’Tornado cash’ is what’s sanctioned. It’s a subtle but potentially pertinent distinction.

Another concern relates to the parallels drawn between Tornado cash and other open-source privacy-focused software, such as encryption software. Some privacy advocates suggest that if the sanctions aren’t removed, encryption software, and sound cybersecurity practices, in general, could be targeted by the same logic and that ‘backdoors’ could be required to be installed. After all, one would imagine that cybercriminals would naturally prefer encrypted and private software with no backdoors.

While some parallels can certainly be drawn Tornado cash and various types of encrypted software and encrypted communication tools, there are also some differences to note. For one, the use of encrypted software and encrypted communication tools are widespread, and it’s fair to say that the vast majority of times people use it, it’s not for illicit purposes. The same cannot be said for Tornado cash, for reasons already mentioned.

Another pertinent consideration is the intended usage of the code. In the past, completely self-executing immutable code has never been able to move money before. Tornado cash has changed that. It moves and allows for the obfuscation of money in a fairly decentralized manner, without any other agent taking custody of the funds. In contrast, encryption technologies, such as encrypted communication software like Signal, don’t themselves move or facilitate the laundering of money (no money is sent on or through the platform). This begs the question as to whether it’s reasonable to treat Tornado cash differently from other technologies on the grounds that it can facilitate the movement and laundering of money?

Blanket Sanctions Unreasonable Counterargument

Pretty much any technology or tool can sometimes be used for illicit purposes. As we previously discussed, it would be quite misleading to suggest that Tornado cash is analogous to many other technologies. This is because the proportion of illicit activity involving Tornado cash is far higher than the vast majority of tools and technologies available and far higher than other payment mediums, such as cash.

As previously discussed, 22% was a lower-bound threshold identified for attributable illicit activity involving Tornado cash. This is already an incredibly high number, but as previously discussed, even it still is a gross underestimate, and 50%+ is more likely. And as over $7 billion USD has been sent through Tornado cash to date, the amount isn’t chump change.

When such a high proportion of activity involving a service is illicit in nature, a blanket sanction seems much more reasonable in our opinion.

But there is an additional reason, in our opinion, why exchanges (including Coinbase) are less than enthusiastic about Tornado cash designation, and as usual, it boils down to money. Specifically, enacting these types of sanctions on individuals inevitably requires more resources, time and personnel from exchanges, and with that, added compliance costs for such exchanges that negatively impact their bottom line. Coinbase’s decision to fund the lawsuit in the Treasury can thus be seen, at least in part, as a financial investment so as to avoid/mitigate increasing compliance costs, which would inevitably cost a lot more than funding a lawsuit in the long run.

Entities that Could be Targets of Sanctions in the Future

There are a variety of entities that we think could conceivably be the target of sanctions in the future. Whether or not certain entities are targeted with such sanctions or not really depends in large part on whether the focus of who or what activity the US treasury is targeting in their mandates stays the same or whether it expands at all.

This is because right now, it appears that the primary reason for imposing such sanctions relates to national security, mitigating the threat of terrorism, mitigating foreign nation-state actors, and efforts to prevent the proliferation of WMDs. The US Treasury is glad that such sanctions may help mitigate some thefts and frauds as well, even when they aren’t related to one of the above scenarios noted above.

But this begs the question: Is the US Treasury interested in ‘cracking down’ on all the thefts and frauds in the cryptocurrency space, even when such incidents aren’t a national security concern? Are they really keen on taking this type of action to mitigate exchange hacks, DeFi exploits, and cryptocurrency thefts from individuals and businesses, even when the perpetrator isn’t Lazarus group and when it’s not a national security concern? What about all the various types of scams, including pig butchering scams which have become incredibly prevalent, and are usually run by organizations and syndicates operating in South East Asia, primarily China, whether the US otherwise has minimal viable avenues to pursue due to jurisdictional challenges?

The answers to these questions will affect who gets sanctioned in the future and who doesn’t. We’ve outlined a few different categories of entities that could conceivably be subject to sanctions in the near future below.

Illicit & Non-compliant OTCs and ‘Nested Services’

With the sanctions on OTCs including Garantex, Suex, and Chatex, the US government has already shown a clear willingness to sanction OTCs that engage in a large amount of illicit activity. It is safe to assume that sanctions on similar types of entities will continue to be introduced.

There are a laundry list of OTCs and Nested Services that have extremely poor or even non-existent compliance policies, and thus far, the US government has only targeted a small fraction of them. Will the scope of who is targeted in the future be expanded? If so, how much? And will they only be targeted with sanctions if they are found to be facilitating a significant amount of illicit activity from a matter that’s a concern to national security?

Major Exchanges

There are no major exchanges that have been targeted with sanctions yet. In our opinion, that could conceivably change in the near future, and some select exchanges that most readers would have actually heard of before could very possibly be targeted. The exchanges that are most likely to be targeted are the ones with the most abhorrent or non-existent compliance policies and the ones that choose to facilitate the largest amount of illicit activity for their own profit. Additionally, by definition, illicit OTCs and nested services use major exchanges for liquidity. What exchanges elect to do business with the shadiest OTCs and how would that affect whether they are subject to sanctions themselves?

Some exchanges are significantly worse than others. If any major exchanges are targeted, in our opinion, OKX and Huobi are a couple of the most likely targets for sanctions; they both have a strong track record of turning a blind eye to money laundering.

Whether the US Treasury is actually going to go this far and sanction major exchanges that many normal people utilize just because of their horrendous compliance programs remains to be seen.

Other Mixers

Other mixing services could conceivably be the target of sanctions in the future. There are a variety of custodial mixing services out there that could be targeted, although whether or not they are targeted may in part depend on whether a significant amount of money is or has been laundered through such mixers in cases that involve matters of national security.

Blender.io is the first mixing service to be targeted with sanctions, but a variety of others similar to it could very conceivably be targeted.

A more interesting discussion is whether or not other non-custodial services may be targeted, such as Wasabi for example.

The reality is that Wasabi is not quite as decentralized as Tornado cash is, and thus some of the legal arguments being put forward in favour of Tornado cash cannot equally be applied to Wasabi.

While both Tornado and Wasabi are non-custodial mixing services, Wasabi mixer does not employ any immutable self-executing code (smart contracts) which Tornado cash does. This is because Smart contracts don’t exist on the Bitcoin blockchain. Wasabi does rely on some level of centralized permission, and in the case of Wasabi wallet, that centralized permission is the zkSNACKs coordinator. Interestingly, earlier this year, the zkSNACKs coordinator started refusing certain UTXOs from registering coinjoins, no doubt due to government pressure. In contrast, no similar function is capable for Tornado cash even if the Tornado cash developers or the Tornado Cash DAO wanted to implement it.

For these reasons, if Wasabi were to be subject to sanctions, there could arguably be a ‘legal person’ to sanction, namely the coordinator. And while Wasabi’s code can be freely, legally copied, and independently run, any other Wasabi coordinators could also be subject to sanctions by the same logic.

Entities that Support Monero Swaps/Trades/Conversions

Exchanges that support trades or swaps for Monero (XMR) could conceivably be targeted for sanctions in the future. The exchanges and services most likely to be targeted include:

- Those with a very poor or non-existent compliance policy that facilitate XMR swaps. This would likely include not having any KYC data on the customers performing XMR swaps, but would also include not taking adequate measures to identify or prevent suspicious activity or transactions and would likely involve being uncooperative with law enforcement as well. A compliance policy runs much deeper than simply having KYC, and there are many things an exchange/service can do from a compliance perspective, even without collecting KYC data.

- Those with a historically high volume of illicit activity and those that have historically been used to facilitate Monero swaps in matters that involve national security (like ransomware incidents).

As usual, it’s likely that only the most egregious exchanges and services would be targeted by such sanctions with the hope that such sanctions will make others “fall into line.”

Tokenlon

As we’ve previously argued, Tokenlon is nothing more than a shady OTC masquerading as a DEX, and the vast majority of its usage is related to money laundering for pig butchering scams while claiming “it’s decentralized” as an excuse (which isn’t even true in the case of Tokenlon anyway.)

While pig butchering scams are now squarely in the crosshairs of US law enforcement, we don’t know whether or not the US Treasury has an appetite for cracking down on them to the extent that they’d be interested in applying sanctions on Tokenlon. If the US treasury does have the appetite for it, it’s very likely that Tokenlon will be the first “DEX” that’s sanctioned. But the reality is the US Treasury might not ever have the appetite for it since pig butchering scams and the scammers behind them aren’t inherently a risk to national security.

Stablecoin Issuers

In our opinion, there’s a chance that centralized Stablecoin issuers, including most notably Tether, could themselves be at some degree of risk of sanctions. However, sanctions against Tether are very unlikely unless the US Treasury expresses an appetite for cracking down on Pig Butchering scams, in which USDT is wildly used. Even if the US Treasury becomes keener on cracking down on such scams, we don’t think sanctions on Tether are overly likely as cryptocurrency holders so widely use Tether for completely legitimate purposes.

It is an interesting thought expert at the very least, as it would likely allow for USDT held by illicit actors to be effectively seized, as the value of the tokens would likely plummet to zero or near zero, and the underlying assets that Tether holds to back these tokens could themselves potentially be subject to seizure.

Additionally, such sanctions may well prove to be more trouble than they are worth anyways – it’s not hard to imagine just how many lawsuits and/or claims there would be to assets by people that happened to hold USDT at the time the sanctions were enacted.

The Decentralization Excuse and Feigning Ignorance

It’s no secret that one of the core reasons for the push toward more decentralized services is in an effort to make the cryptocurrency space less prone to government oversight and regulation since there may be no entity responsible for controlling or stopping a decentralized service, and thus ‘can’t’ be regulated.

Increasingly, “decentralization” is used as an excuse in an effort to avoid compliance obligations, just as illicit exchanges often feign ignorance about the source of suspicious funds by claiming that they can’t inherently know who controls self-custodial wallets on the blockchain.

Decentralization isn’t an excuse to be used to subvert compliance obligations, and as we’ve discussed, decentralized services aren’t always as decentralized as they claim; it all too often is just a façade. Some actions, including sanctions, can arguably be taken against decentralized services, but whether or not the US Treasury has the appetite for doing so remains to be seen.

Note: Nothing in this article is to be construed as legal advice or legal opinion.