Romance scams, which often involve a scammer impersonating someone as part of the scam, aren’t new by any means, but a new breed of romance scam has become incredibly prevalent over the past few years. This breed of romance scam has been referred to as a ‘pig butchering scam’ due to how the scam operates.

What Is a Pig Butchering Scam and How Do They Work?

A ‘Sha Zhu Pan,’ which translates as ‘Pig Butchering Scam,’ is a type of romance scam that commonly originates in countries in South East Asia, most often China. These are large operations, run in a corporate-like structure, often with employees and offices, and are not run by single individuals.

The name of the scam derives from how these scams operate. A ‘host’ works to build a relationship and rapport with a victim (‘pig’) before scamming them and encouraging them to invest large amounts of money in an online investment platform (which is operated by the same group of scammers) that they refer the victim to. The ‘host’ does not immediately try to scam a victim upon initiating contact. They take their time, waiting weeks, or sometimes even over a month, before slyly introducing the pig to the scam that will result in them being scammed and losing a lot of money. Similar to fattening a pig up before slaughter, hence the name. Once the victim starts ‘investing’ in the scam, the victim won’t immediately know it and will often put more and more money into the scam. The ‘host’ will continue to milk the victim for all they’re worth.

While the ‘host’ will indicate that the victim will need to invest a decent amount of money ‘if they’re serious’ about earning money, if the victim starts out with a small investment, such as a $1-2k USD of cryptocurrency, the victim will usually be able to ‘withdraw’ the majority of it from the platform. The scammers do this to instill confidence in the victim about the legitimacy of the platform so that they feel comfortable ‘investing’ significantly more money in the future.

Once the victim deposits a larger amount of money, such as tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, the victim won’t be able to withdraw the money due to various types of excuses the scammers come up with. What will happen though, is that the scammers will entice the victim to deposit more money if they want to get any money out of the platform. Scammers have an infinite number of excuses they use in this regard, such as the “IRS tax,” which conveniently cannot be deducted from the “profits,” is paid in cryptocurrency, and even applies to non-US persons! Locked investment accounts, service fees, lending fees, server downtime, and technical issues are also common excuses that are concocted.

When larger amounts of money are invested, sometimes victims are able to get a very small portion of their principal out (the ‘profits’ the victim ‘earns’ on the platform don’t actually exist), but only if it’s a very small amount (e.g., 2%-5% of the amount investment) and only if the scammers genuinely think the victim is going to invest considerably more money in the future as well. This is because it’s a cold, financial calculation on the part of the scammers. Do they want to risk refunding the victim a small amount to keep the relationship intact? If the amount the victim is requesting is small, and if the scammers stand to profit considerably more in the future, it can be well worth the ‘risk.’ If those variables change for whatever reason i.e., if it’s evident the victim is already suspicious, or the victim is trying to get a large chunk ‘out’ then the risk of giving money back to the victim just isn’t worth any potential future money they may be able to get.

Once the ‘pig’ starts ‘investing’ money, the ‘host’ will continue to encourage them to invest more and more typically over a period of months. The victim will usually have a separate line of communication with ‘customer support’ from the platform (obviously not aware that the ‘host’ is in on it). Eventually, the victim comes to the realization they’ve been scammed when they are unable to withdraw funds from the platform.

There are many fraudulent investing platforms that have these same characteristics whereby you can send cryptocurrency in but can’t get it out. A core defining feature of the Sha Zhu Pan is the way the victim comes across the scams to begin with (not through paid advertising or marketing, but by the scammer appearing to naturally establish a connection with the victim, which they ‘work’ on slowly, building rapport with a victim), the way the ‘host’ patiently works on the victim over time, along with the sheer size and number of employees involved in this scam which has a corporate-like structure, with different people responsible for different aspects of the ‘business.’

Characteristics of Sha Zhu Pan Scams

There are a variety of indicators and techniques used which may indicate that you’re a prospective target in a Sha Zhu Pan. These include:

- The ‘host’ will often greet you ‘good morning’ or ‘good evening’ each day. They will generally talk with you every day as well.

- They aren’t afraid to share pictures. Of something they allegedly bought, somewhere they visited, or food they cooked that often looks professional (these photographs are often staged by corporate, and the host has a large collection of photographs to work with).

- Both men and women are targeted (and the ‘hosts’ use both male and female profiles).

- They express interest in ‘learning’ something from you (e.g., improving their English) but also have things they want to ‘teach’ you.

- They have their own business, which largely won’t be possible for you to verify independently.

- The person is attractive.

- He or she talks a lot about their beliefs and where they believe they are going in life.

- They ask what your goals and dreams are and they encourage you to ‘dream bigger.’

- They casually mention spending significant amounts of money on material items. This is done in an effort to belittle the victims insinuating they aren’t a suitable romantic partner if they don’t have enough money for their lifestyle.

- In a week or two, but sometimes a month or longer, he or she will bring up forex or more often cryptocurrency investing or trading.

- They’ll keep bringing up investing and crypto trading as being something they’re passionate about while obviously hoping that you will ‘share’ that passion by investing your own money.

- Mentions that they’ve gotten into Crypto or Forex trading, that they’ve been earning a good amount of money doing so, and suggest you ‘check out’ the investment or trading website that they refer you to.

- Most times, in order to fund the ‘investment platform’ account, you need to deposit cryptocurrency. This, in turn, will allegedly allow you to ‘trade’ or ‘buy’ whatever investment package, arbitrage trading package, or whatever “new upcoming token” they have listed on the platform’s website.

- They’ll casually mention a few exchanges where you can buy real cryptocurrency depending on your jurisdiction (e.g., Coinbase). Then it’s as simple as withdrawing the cryptocurrency to the address listed on the website.

- Your ‘account’ can sometimes be funded via a wire transfer. For reference, these bank accounts you’d ended up sending wires to are sometimes owned by money mules, or in other cases, the account owner ‘sold’ their account to the scammers (i.e., an international student that leaves the US).

- They have a friend/brother/uncle that taught them what they know.

- Belittles you for not investing ‘enough.’ “You got to spend/invest money to earn money.”

- You’ll ‘trade’ with him or her together, taking their ‘trading advice.’ You’ll ‘earn’ profits together. You’re happy with the performance because, over time, your ‘account balance’ will increase substantially. As an FYI, however, your ‘account balance’ doesn’t actually exist because the scammers control the platform, and there are no trades actually being conducted (the platform merely gives the appearance of it).

- The platform may indicate you’ve suffered a big loss and that you need to make up the shortfall. The scammer will suggest putting more money in or ‘borrowing’ from the website, or he or she may be willing to lend or even give you money themselves (i.e. the scammer may indicate they are willing to pay ‘half’ of what you put in — your ‘balance’ will increase of course once the scammer ‘puts in their half’, but remember they control the account balance so your ‘account balance’ has no relevance — they aren’t actually ‘lending’ any money at all.)

- They trade on an irregular schedule and use charts and information they obtained from ‘sources’ they have.

- They question your commitment to the relationship, get upset easily, shame you, belittle you, and do anything else that makes you feel small or inadequate.

- They’re happy to send photos and sometimes do voice calls, but they always have an excuse for not wanting to meet up in-person or doing a video call. This is because they can’t; they aren’t who they say they are — sometimes not even the same sex that they suggest. (although rare, some ‘hosts’ do actually do video calls – the vast majority don’t, however.)

- He or she is almost always available to chat, even at seemingly odd hours.

- They give the appearance of being helpful and courteous, even if you level accusations against them.

- When you put a few hundred dollars in, you can take the money out without issue. Even a couple thousand, you can usually withdraw a good portion of it. If you invest larger amounts, the slaughter starts; you won’t be able to withdraw. The excuses start and will never end.

- The platform offers incentives and bonuses if you invest very soon by a set date (like tomorrow). This is so you FOMO in, don’t have time to do your own research, and don’t have time to ask friends/family, or even really ask yourself, ‘is this legit?’ But no worries, your new love interest vouches for this platform.

- They will come up with excuses to get you to put in more money. Initially, it’s because your investments have been doing so well, so you need to invest more money to make money. Eventually, there will be “taxes,” “compliance fees,” “lending fees,” “processing fees,” or your account gets “frozen” and you have to pay to “unfreeze” it. They have an unlimited number of excuses they will use to get you to put more money in from outside of the platform. As you can probably guess, these fees cannot be deducted from your account balance (but they won’t tell you about this until the time comes).

- Suddenly, you have 10 days to pay “unpaid fees” or your account balance will start being deducted 5-20% per day until you’re compliant.

- Customer support will sometimes tell you to ‘reverse’ or ‘cancel’ a payment you just made because the ‘address is no longer in use’ or because you sent it to the wrong address (that they provided you). Such cryptocurrency transactions are not reversible. Eventually, the issue will be escalated to management — after a while, they are willing to ‘write off 20-50%’ as a loss, provided you pay the ‘remaining’ 50-80%.

- The value of your investment has already increased multiple times, so the victim can’t justify giving all that up. The scammers keep coming up with more and more excuses, often putting a victim into significant debt who will sometimes take out loans from family members or their bank, until they’ve been slaughtered and bled dry.

Who’s Operating these Scams?

Large organized groups of scammers operating primarily out of South East Asia, often China. The ‘hosts’ are specifically trained on how to deal with certain types of people with different profiles. There is a lot of psychology behind it that they learn how to exploit for financial gain.

How Common are Pig Butchering Scams?

Common. To provide an idea of the scale, they currently constitute approximately 35-40% of legitimate inbound inquiries we receive at Cryptoforensic Investigators more than any other category of cybercrime, including hacks.

Even if you don’t own cryptocurrency, it’s likely that at some point, you’ve been contacted by someone that is part of one of these schemes on multiple occasions. Maybe you’ve even had a brief conversation with them, which hopefully resulted in you cutting off contact under the suspicion of it being a scam.

‘Hosts’ get in touch with prospective victims in a number of ways. One of the most common ways is through dating applications like Tinder, Hinge, OkCupid, etc. Ever started talking to someone on one of these sites that quickly wanted to move the chat off-platform and thereafter seemingly ‘casually’ mentioned that they were a ‘cryptocurrency investor?’ If that sounds familiar, it’s likely you were speaking with one of these scammers.

Granted, there are plenty of other ways scammers get into contact with new potential victims, including social media, random outreach, video games, and ‘referrals.’

How Much Cryptocurrency Has Been Lost Due to Sha Zhu Pans?

A lot. On the low end, Billions of US dollars worth of cryptocurrency has been lost to pig butchering scams in 2021 alone, but 2021 losses are more likely into the tens of Billions USD. The existing hard data in official sources on how much has been lost to such scams grossly underestimates the losses due to this type of fraud, but let’s start by taking a look at what data does exist.

In 2021, the FBI reported that $1 Billion USD was lost to romance scammers (in the US) while noting that it was likely that ‘many more losses went unreported.’ While the FBI does specifically call out and mention cryptocurrency in his post, it’s unclear just how much of this loss came in the form of cryptocurrency. Data from the FTC suggests that the FTC logged losses of $139 million USD in crypto-related romance scams in 2021.

While we can’t put a firm number on the amount lost, it’s safe to say both these loss figures are gross underestimates of the amount of money that has been lost in crypto-related romance scams, the majority of which is being lost in pig butchering scams these days. This is due to a variety of reasons:

- People all too often don’t bother to report their losses to law enforcement under the impression that it’s futile or that nothing will come of it. When someone has lost a few thousand dollars due to this type of scam by scammers almost certainly in another country, it’s generally not feasible for law enforcement to pursue it as the resources spent on it could far exceed the amount of that loss quite easily. However, if people don’t report their losses to a given law enforcement agency, then that agency doesn’t have data on it.

- The law enforcement agency the victim reports to. The FBI? Their local police office? Or are they reporting or the FTC? Another agency entirely? Not everyone even within the US alone that reports a loss to US law enforcement reports to the FBI in particular.

- The Country of residence of the victim. The loss data the FBI has comes from US-based victims. Victims from elsewhere, whether the UK or Zimbabwe, generally don’t have cause or reason to report to a US law enforcement agency, nor would US law enforcement likely have jurisdiction to investigate if there is no genuine connection to the United States. Obviously, there are many non-US victims, and thus the data the FBI has would naturally underrepresent the losses incurred by victims around the world.

- Improperly formatted law enforcement reports. If the loss isn’t properly identified or incorporated into the submission and/or if there is insufficient data to substantiate the loss, it’s possible that some law enforcement may factor that loss value into their calculations. Additionally, some agencies may elect to review or vet reported losses in some way before factoring them into totals or otherwise categorizing the reports.

- Pig butchering scams are not well-branded relative to other types of investment scams. The ‘host’ will typically direct the victim to a website that has a very limited online presence and recognition and isn’t well talked about, as the scam does not seek to market itself online. People almost always only come across the scam upon being referred to the website by a ‘host.’ In most cases, while the fake platform will have a login, in some cases, we’ve seen cases where there’s no actual way for someone to independently ‘sign up’ if they wanted to whereby an ‘account’ can only be created if the ‘host’ has an account created for the victim. The website domains of these platforms also come and go all the time. This can be contrasted with a more well-branded investment scam such as Arbitly[.]io as but one of many examples since quite a few people talk about this and Arbitly and its domain was marketed and advertised. Thus, we have a much better idea of the amount victims lost in the Arbitly scam, than some random, perhaps Chinese-looking website that saw minimal traffic, and which are a dime a dozen.

- The amount of reported losses reported to us in 2021 arising from Romance-related frauds alone, the vast majority of which are Pig butchering scams is multiple times higher than the FTC-reported losses of $139M USD. Losses reported to us that fit this categorization from 2021 are in the $500 Million USD range. Clearly, the FTC’s figures are a gross underrepresentation of such losses if the losses reported to a small company like us alone already exceed that figure multiple times.

- Obviously, the vast majority of victims of Pig butchering scams do not report their losses to us, and thus we can safely conclude that losses are multiple times this ~$500M figure. While considering this figure, keep in mind that we publicly state on our website that we do not work on cases where the loss is under 100k USD, which already filters out a large portion of victims. If losses under 100k were reported to us in proportionate amounts, there’s no doubt this figure would be considerably higher.

- On-chain data. One of the hallmarks of pig butchering scams is address reuse. Scammers (or the ‘platform’) often don’t bother to use a unique address when getting the victim to ‘deposit’ funds. They often use the same address(es) for multiple victims. And funds often end up getting routed through the same intermediary/consolidation wallets, which may be scammer-controlled as well. Thus, when looking at a given address that a reported victim has sent funds to (typically from an exchange account of theirs like Coinbase, Binance, Crypto.com or Kraken exchange), in many cases, addresses will also have a considerable number of deposits from such centralized cryptocurrency exchanges that aren’t attributable to the reported victim. Ergo, the other deposits are more often than not attributable to other victims of the same scammers that we don’t know about.

Once we factor in these unreported losses, factoring in losses reported by our partners, while reviewing intermediary wallets that are very likely used by the same scammers in an effort to obfuscate the flow of funds, we can already get a much better idea of the true extent of losses in such scams. Very conservatively, billions of dollars of cryptocurrency in 2021 alone. Much more likely into the tens of billions of dollars just in 2021.

Collectively, losses are incredibly high, and most people don’t know the true scale of it because there is no centralized source gathering all the data associated with crypto loss due to pig butchering scams.

Usually, the victims are not particularly well-adept or as knowledgeable about cryptocurrency as most cryptocurrency investors. In some cases, they have no prior cryptocurrency ‘investing’ experience at all and were goaded into investing by the scammer. Victims are not all elderly as you might imagine; far from it. There are certainly many elderly people and middle-aged people that are targeted (both men and women), but it’s common to see victims in their 30s and even 20s as well. Naturally, this is a barrier to more widespread adoption of cryptocurrency if people’s first exposure to cryptocurrency is as a scam victim.

How Do the Perpetrators Behind Such Scams Launder Cryptocurrency?

The ‘host’ directs the ‘pig’ (victim) to first acquire cryptocurrency on a legitimate exchange like Coinbase or Crypto.com. Then, they convince the victim to withdraw that cryptocurrency and ‘deposit’ it into a fake cryptocurrency exchange or investment platform that they refer the victim to. Sometimes it’s for the purpose of ‘trading’ on the platform (no actual trades happen despite what the user’s account says otherwise) or in some cases to acquire a ‘new’ cryptocurrency only available on the platform, but which they claim has very high investment potential. As an FYI, in our experience, the scammers don’t even bother to actually create any new token or cryptocurrency at all — they just make the claim that there is one.

In our experience, victims almost always ‘deposit’ (or send) one of four different cryptocurrencies to the scammers:

- Bitcoin (BTC)

- Ethereum (ETH)

- USDC (ERC-20)

- USDT ‘Tether’ (ERC-20 or TRC-20 specifically)

If the victim ends up sending BTC, ETH or USDC, virtually 100% of the time, the scammers will swap the funds to USDT through a “decentralized exchange” known as Tokenlon, which I will talk about in more detail later. This is sometimes done directly from the scammer-controlled wallet, while in some cases the funds pass through an intermediary or consolidation wallet controlled by the scammers.

In a good portion of cases, not quite 100% of funds will be converted to USDT. In many cases, there are some small deposits often back to the same types of exchanges that funds were received from, such as Coinbase, crypto.com and Gemini. However, these small deposits are almost never associated with accounts belonging to the scammers, but more often victims that were able to ‘withdraw’ a small portion of what they ‘invested’. It’s not uncommon for scammers to ‘process’ these ‘withdrawals’ as it will give victims a sense of confidence that the platform is safe so that they can feel confident investing considerably more in the future. Obviously, the scammers will not process any withdrawals if they sense any hint of suspicion on the part of the victim or if they don’t otherwise believe the victim will deposit more money.

Once the scammers have USDT (after converting to it via Tokenlon, or via receiving USDT from the victim directly), the typical pattern we see is that the USDT flows through some intermediary wallets usually controlled by the scammers, and from there, most funds are usually sent to Asian OTCs or brokers (trading in China is predominantly OTC). While funds do often eventually reach a variety of centralized cryptocurrency exchanges, most often the accounts are owned by the OTCs, or occasionally by the counterparties that the OTC/P2P transacted with.

In China, and some countries in Southeast Asia as well, USDT is largely regarded as the ‘base’ currency and medium of exchange (so far as cryptocurrency is concerned anyway) which would be used for most different types of trades, business transactions, and payments. This is why the scammers are always focused on converting to USDT specifically.

Illicit Actors, Exchanges, and Money Laundering

As most people can probably imagine, the OTCs and P2Ps (that can sometimes be challenging to identify) that do business with the scammers would generally not be regarded as compliant. They make good money off of it themselves, so usually end up turning a blind eye to such activity or will choose to believe nothing shady is going on. Obviously, some OTCs and P2Ps facilitate a higher proportion of illicit activity than others that may facilitate very little or none. Some OTCs knowingly facilitate illicit volume or choose to believe that Anti-money regulations simply don’t apply to them. Suex and Garantex are some of the more notable OTCs that sanctions and enforcement have been taken against (granted these OTCs were primarily laundering money for actors in Eastern Europe, especially in Russia, not Sha Zhu Pan scammers).

A similar case can be made for exchanges. Some major exchanges choose not to implement a real compliance program (while of course claiming they adhere to rigorous compliance standards) and choose to turn a blind eye to this type of activity or pretend it’s not happening altogether. The reason is of course money and trading volume – there’s a market for non-compliant exchanges that won’t bother account holders about illicit funds and questionable or non-existent compliance practices.

While many exchanges have perfectly adequate compliance programs, the ‘compliance department’ of certain, select exchanges is a joke (if they have a compliance team at all). Some exchanges aren’t responsive to law enforcement at all. Others try to make law enforcement ‘jump through hoops.’ Some aren’t responsive to subpoenas. They employ a variety of ‘jurisdictional gymnastics’ to make it difficult to seek information with them or otherwise hold them accountable. Despite poor compliance track records, such exchanges will often publicly regard themselves as being highly compliant with a robust AML program, when the reality couldn’t be further from the truth. This is something we’ve referred to before as compliance theatre.

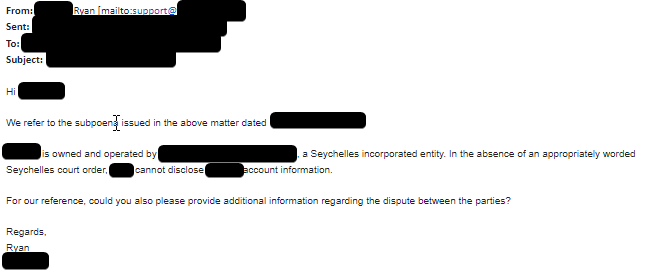

To show this in practice, we’re to provide a redacted example whereby a major cryptocurrency exchange (which will remain unnamed) that is registered in Seychelles, and which received ~55 Bitcoin directly from a fraudster-controlled account, was sent a US subpoena as part of the scope of a civil fraud lawsuit. This exchange was served with a valid US subpoena. Their response? They declined to provide any information unless they were served with a valid subpoena from Seychelles specifically, as shown below:

Response from a certain ‘Seychelles-based’ exchange when served with a US subpoena

As this exchange was registered in Seychelles, they would be technically correct that they weren’t legally obligated to respond to a subpoena from outside of Seychelles. But this type of response (which is by no means unique among less-than-cooperative exchanges) is not the most practical response/policy to have for a variety of reasons:

- They are registered in Seychelles but aren’t, in practice, located in Seychelles otherwise. Their Seychelles registration is effectively a ‘shell company.’

- This is a ‘global’ exchange that serves clients all around the world (they have since restricted US persons from using them), obviously not just Seychelles, otherwise, they’d have almost no clients.

- While obtaining a subpoena from Seychelles is possible of course, it is incredibly burdensome from both a time and cost perspective; it would add tens of thousands of dollars to the cost (+ a few months, best-case scenario).

- The exchange was actively under investigation by a US government agency. One would imagine that if they were subject to such a probe, they would be more compliant and cooperative. Evidently, that was not the case here!

This situation is by no means unique. Creating needless but arduous and expensive obstacles to overcome is actually a ‘great’ technique that less-than-compliant exchanges often use to increase the amount of fraudulent activity on their exchange (which benefits their bottom line) and helps to increase the amount of fraud happening in the cryptocurrency space overall (as if there isn’t enough of it already?) since laundering becomes easier and there are more businesses out there willing to facilitate it.

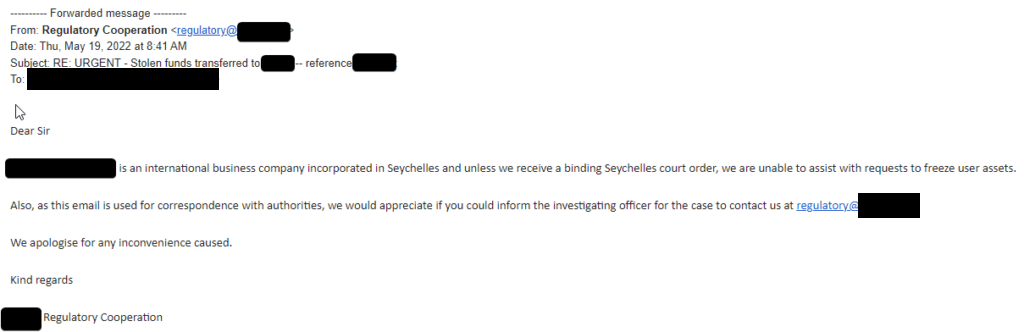

Another case in point happened just today. We informed a different ‘Seychelles-based’ exchange, that operates globally, and promptly notified them that stolen funds had just been transferred to them from a wallet controlled but the perpetrators behind a theft. We suggested that the exchange may wish to freeze the account pending law enforcement contact, and provided both a police report, as well as applicable evidence to the exchange showing that the funds were indeed stolen. Their response is below:

Redcated response from Seychelles-based exchange when notified of stolen funds being deposited

This exchange often isn’t responsive to notifications of illicit activity or even requests from law enforcement. In this case, they at least ‘responded’. The core issue is that this exchange’s ‘compliance program’ is an embarrassment and a facade (really — they only cooperate if a Seychelles court order is obtained despite being an ‘international business company?’), they don’t use any mainstream forensics or transaction monitoring tools (which is common practice in this industry now, except for the least company exchanges of course), and evidently don’t do anything when notified of illicit activity.

Cryptocurrency can obviously be transferred to other individuals and entities across borders just as easily as if there were no borders at all. And a good portion of exchanges services customers from around the whole world as well. Thus, it would logically be a more reasonable policy to be responsive to subpoenas from multiple jurisdictions instead of just the jurisdiction they’ve chosen to register in. The reality, however, is that some exchanges employ strategies in an effort to be as uncooperative as possible, as there is ‘demand’ for illicit trading volume, and exchanges that find a way to service that ‘market,’ can profit as a result.

Tokenlon – Not Quite a DEX Like They Claim

Many cryptocurrency investors are by now familiar with decentralized exchanges like Uniswap and 1inch that utilize a variety of smart contracts to facilitate trade in a relatively decentralized but also transparent fashion. As some readers may know, a central tenet of a decentralized exchange (DEX) is that they are to a large extent immutable because the smart contracts upon which they run are immutable and not susceptible to censorship (e.g. regulations) and thus even if the interface for a given DEX was no longer available, users could still interact directly with the smart contracts to trade.

Description of Tokenlon from the Tokenlon website

The ‘money people’ involved in Sha Zhu Pan scams rarely use any of the decentralized exchanges you’ve likely heard of before. Essentially, they exclusively use a DEX (and wallet) called Tokenlon / imToken which the vast majority of readers probably haven’t heard of, much less use or know someone that uses it themselves.

Tokenlon (associated with the imToken wallet, and the company imToken PTE Ltd.) bills itself as a ‘decentralized exchange’, but there are some notable issues with this claim, in addition to notable differences from other more popular DEXs like Uniswap.

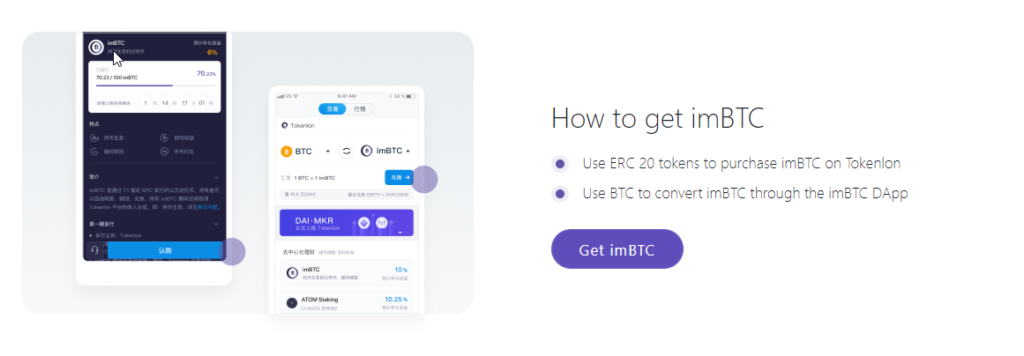

Tokenlon BTC swaps

The first glaring issue is that Tokenlon claims to have a decentralized exchange/service that supports Bitcoin. Tokenlon refers to this as the ‘imBTC DApp’ (decentralized application) and one can use BTC to obtain imBTC right through this ‘DApp’ per their website.

Tokenlon’s imBTC Dapp, per the Tokenlon website

Uniswap, 1inch and the other DEX’s you’ve heard about do not support Bitcoin. The reason for this is that smart contracts are a central aspect that allows a DEX to function in an immutable manner. As some readers here hopefully know, Bitcoin does not support smart contracts! Thus, (real) Bitcoin simply cannot be traded on any decentralized exchange that uses smart contracts.

Instead, Tokenlon is acting much more like a centralized OTC desk or exchange, while pretending to be a decentralized exchange so as to pretend that compliance and Anti-money laundering (AML) regulations simply aren’t applicable to them (for facilitating conversions from BTC to USDT). To demonstrate this, I’m going to explain in an example exactly what happened in a BTC-USDT ‘decentralized’ swap on Tokenlon:Tokenlon/IMToken BTC deposit:

Tokenlon/IMToken BTC deposit: defbf993f6c34c90090d193314da12c8b0c51f7f50ee4fc0b3e677a5dc0b33ae

Deposit amount: 9 BTC

Transaction time: 12/22/2021 07:03 UTC

Approximate USD/BTC price at time of the transaction: $49,249.47 USD

Imputed value of 9 BTC at time of the transaction: $443,245.23 USD

Using this data, we can take a look at outbound transaction(s) from the wallet owner and ultimately the inbound transactions received in USDT in return. To do this, it’s critical to understand that it actually starts with a BTC-imBTC swap, and imBTC-USDT swap(s) usually follows that very shortly thereafter. The imBTC contract is 0x3212b29E33587A00FB1C83346f5dBFA69A458923. imBTC is a token on the Ethereum network pegged to the price of BTC that is issued and managed by IMToken Pte Ltd (Tokenlon). In the transaction above, the wallet owner sends 9 BTC to Tokenlon. When the 9 BTC is received by Tokenlon, shortly thereafter Tokenlon issues and sends around 9 imBTC, less fees, to the destination Ethereum address the sender provided from the imToken wallet application.

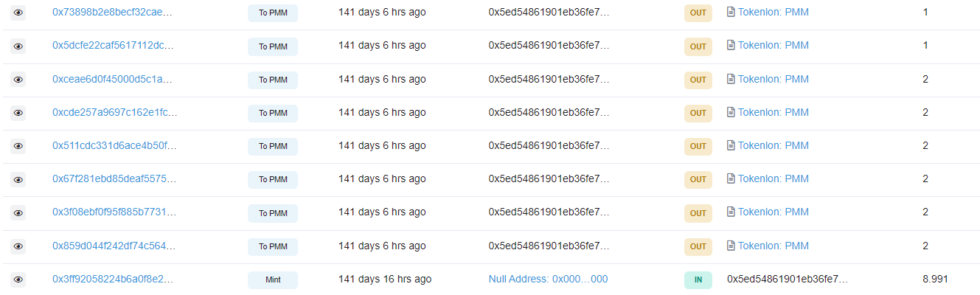

In this case in particular, we can see the issuance of 8.991 imBTC in transaction 0x3ff92058224b6a0f8e290e96a41dd479070777ef7750bd622dd1eae35ab66a0c at 07:28 UTC to 0x5ed54861901eb36fe7771c90fa13e646a141d851. This is the corresponding imBTC output the scammer received.

The next question that arises from this is “what happened to the imBTC?” The answer, in our experience, is that it’s always immediately or almost immediately sent to Tokenlon to be swapped for USDT. More specifically to Tokenlon contract 0x8d90113a1e286a5ab3e496fbd1853f265e5913c6 which Tokenlon likens as a DEX. Let’s take a quick look on Etherscan about the flow of imBTC in this example we are talking about:

Flow of imBTC into the wallet, and out to Tokenlon’s DEX where the imBTC is swapped for USDT.

As you can see, the imBTC sends to Tokenlon (in exchange for USDT) were done primarily in batches of 2 BTC each. It was likely done in these amounts instead of higher amounts so as to help avoid price slippage.

The amount of imBTC going out adds up to an amount over 8.991 imBTC since the wallet had a balance in excess of 8.991 BTC before this series of imBTC-USDT swaps started, and thus the wallet owner chose to send more than the 8.991 imBTC they had just received. The wallet was by no means a single-use ‘burner’ wallet. On the contrary, this wallet received a total of 165,863,347 USDT from since its inception, and most of that USDT came directly from Tokenlon.

Tracing the imBTC-USDT swaps themselves is relatively easy and is similar to tracing transactions on an actual decentralized exchange like Uniswap. We can take a look at the first imBTC-USDT swap by following the 8.991 imBTC deposit here – https://etherscan.io/tx/0x859d044f242df74c5649a29dce404d7f661422285bef1c051b93491e65fbe608 . After depositing the 2 imBTC, the wallet receives 96,554.58 USDT to the same address. Looking at other imBTC Tokenlon deposits will give you the same result – funds being swapped to USDT and sent back to the wallet owner’s address. And the USDT proceeds to be laundered from here in ways that were previously described.

There are two core indicators that would suggest Tokenlon is not really decentralized at all in this scenario, but rather is operating as a centralized OTC service that is masquerading as a decentralized service, DEX, or dApp, and that they have simply chosen to ignore any compliance and anti-money laundering obligations they have as a money services business under the guise that “everything is decentralized” and that they would be powerless to mitigate or prevent this type of activity (which would be unequivocally false).

There are multiple points of centralization pertaining to the initial BTC-imBTC conversion. As mentioned previously, this swap cannot be done either in a decentralized manner nor can it be done immutably through smart contracts as smart contracts don’t exist on the Bitcoin blockchain!

The first aspect of centralization relates to the wallet application and interface itself, and how the request made by the wallet owner is submitted. The wallet application interface must be used if one wants to swap BTC for imBTC and receive freshly minted imBTC in the process. Tokenlon doesn’t do any due diligence or compliance checks on individuals simply because they want to swap BTC for imBTC.

In order to receive freshly minted imBTC, the wallet owner must first receive BTC in the BTC address on their imToken (self-custodial) wallet. From there they input into the wallet interface the amount of BTC they want to send to be converted to imBTC, and the app provides the amount of imBTC the user can be expected to receive into their ETH address in their imToken wallet in return. The app also provides the destination the imBTC will be sent to, which the imToken app grabs from the user’s imToken wallet. The user then hits the ‘mint’ button. Once the user hits the ‘mint’ button, three things happen:

- The corresponding amount of BTC is sent from the user’s imToken wallet, to a wallet address controlled by Tokenlon (currently set to 3JMjHDTJjKPnrvS7DycPAgYcA6HrHRk8UG). This is a wallet controlled by imToken Pte Ltd, not any smart contract, and imToken Pte ltd has custody and control of this wallet, among other addresses listed here.

- Tokenlon records the interaction in their [centralized] database. While the transaction ID associated with the BTC transaction is present on-chain, much of the data from the interaction is not (there is some data in the RETURN_OP field). The data from the transaction and the user submission is not recorded in a smart contract nor is it recorded when sending or receiving any Bitcoin.

- Tokenlon waits for the BTC to be received, and for a few confirmations on the Bitcoin blockchain. After a sufficient amount of time passes so as to allow for these confirmations, Tokenlon mints the corresponding amount of imBTC, sending it to the destination address that they previously recorded from the submission the wallet owner previously sent via the imToken wallet application. The imBTC minting is done through a smart contract, but only when the conditions that Tokenlon sets have been met, and which are subject to change at Tokenlon’s discretion (i.e. the minting does not occur in an immutable manner).

In terms of what happens to the BTC that Tokenlon has received, that corresponding BTC is now an asset under the custody and control of Tokenlon (much like a centralized exchange), for which Tokenlon has a corresponding liability to anyone that may want to redeem the imBTC for BTC in the future.

Normally select imBTC token holders provide the necessary liquidity here and take advantage of arbitrage opportunities as one would expect, but Tokenlon could always use its BTC reserves to boost the price of imBTC if the price is falling too far below the price of BTC itself as a result of the scammers continuously liquidating imBTC for USDT, and this potential for price stability of the token they issue is another centralization aspect.

If this conception of price stabilization sounds similar to you, that’s because it is. Many centralization USD-pegged stablecoin operators like Tether do the exact same thing and use assets under their control to help stabilize the price of their stablecoins. imBTC is simply a centralized stablecoin pegged to the price of BTC rather than USD.

The scammer then swaps the imBTC, or part of it, for USDT via Tokenlon’s DEX. The imBTC-USDT swap does indeed utilize smart contracts, although more research needs to be done to assess if Tokenlon’s DEX exhibits the same degree of immutability as other DEX’s. The imBTC-USDT swaps are done in a similar manner as ETH-USDT and USDC-USDT swaps, which we get into in more detail below.

ETH-USDT, and USDC-USDT Swaps via Tokenlon DEX

So, now that we’ve discussed exactly how scammers are effectively swapping the BTC they receive from scam victims for USDT via Tokenlon using the imBTC token, we can discuss how they also swap the ETH and USDC they receive from scam victims, and swap to USDT. The elements and features of these swaps are effectively the same as the elements of any imBTC-USDT swap on the Ethereum blockchain.

The wallet sends funds to the applicable Tokenlon smart contract and automatically receives USDT back in return (in the same transaction, just like on Uniswap). Yet another aspect demonstrating the lack of decentralization even amongst the transactions that happen solely on the Ethereum blockchain through Tokenlon smart contracts relates to the minimal number of liquidity providers.

There are considerably few liquidity providers that provide the liquidity to facilitate the transactions the scammers perform. The liquidity providers must provide the USDT liquidity that the scammers want, after which point the LPs will eventually want to realize fees and/or spread earned from providing that liquidity. Given that there are relatively few liquidity providers (it’s not clear what private deals LPs make with Tokenlon, if anything), it raises the question of whether or not these swaps could also be considered effectively OTC trades given the centralization of liquidity.

Questionable Liquidity Providers

Tokenlon is not a particularly popular ‘DeFi’ platform overall, which is why you probably haven’t heard of it before unless you are already familiar with investigating these types of scams, or work in a cryptocurrency-related compliance role, in which case, you’ve very likely heard of them. Social media reveals very little chatter about them. When doing a Google search of ‘Tokenlon reddit’, their practically empty subreddit is the #1 result, and this is the #2 result.

Tokenlon & the imToken wallet has incredibly low use outside of select countries in Southeast Asia, and of the activity that Tokenlon does see, it should be evident by now that a lot of it is fraudulent. So who are the liquidity providers that are providing billions of dollars of liquidity on Tokenlon anyway? Why are they providing billions of dollars of liquidity given the nature of Tokenlon’s business, in conjunction with far high volumes than what would be expected given Tokenlon’s minimal social activity? Do the Tokenlon liquidity providers know about the real nature and amount of relatively high amount of fraudulent activity that Tokenlon and the imToken wallet facilitates?

To us, it appears very likely that the LPs know exactly what is going on and are fully aware amount how Tokenlon is almost always used in Sha Zhu Pan’s, and elect to do business with Tokenlon and provide large amounts of liquidity anyway to make a quick buck. Given the scale at which these LPs (which include some large investment funds) operate, it seems unlikely that they did not do any due diligence into Tokenlon’s business.

It seems much more likely that the LPs are well aware of this activity, and are effectively complicit in the scheme, as it’s certainly profitable for them to provide this liquidity. The scheme is used over and over again by scammers to acquire USDT, which as mentioned is regarded as the ‘base currency’ in China, and this USDT is subsequently laundered primarily via OTCs in Southeast Asia.

Legal Recourse

A common method of recourse in matters involving cybercrime, including Sha Zhu Pan scams, is law enforcement. This would typically entail trying to better identify, and apprehend the person(s) responsible, and in the case of pig butchering scams, take down the entire operation (not just apprehending the ‘host,’ who is essentially just a pawn). However, there are numerous challenges that make the law enforcement route particularly challenging:

- Jurisdictional Issues. Many Western law enforcement agencies don’t have the best relationship with Chinese law enforcement. Some have better relationships than others of course, but in general, there is not much in the way of collaboration and joint efforts regarding mitigating, reducing, and pursuing cybercrime.

- Given how predominant OTC trading is in China, and the lack of regulation, it may be more difficult to identify parties involved in the laundering.

- A good portion of Asian exchanges and OTCs all too often turn a blind eye to this type of activity and/or don’t have an adequate AML program (usually because it’s more profitable for them if they don’t). These exchanges and services may not even be responsive to law enforcement when queried, and if they are, it’s not uncommon for them to try and get law enforcement to ‘jump through hoops.’ Law enforcement has better things to do than hoop-jumping of course.

- While Chinese authorities do sometimes pursue these types of scams, communication alone can be challenging. If the scam is being operated in China, and Chinese authorities try to pursue it, they’re not necessarily doing so in mind with recovering funds for the victims here, especially given that those victims typically reside in foreign jurisdictions (i.e. outside China). They may be focused on getting the scam shut down and seizing/keeping funds themselves; the number one priority for China is China, not you.

Hence, civil proceedings can be more practical, but can also be far more costly for any potential victim, as such proceedings are likely to cost well into the 5-figures USD, but very possibly 6-figures USD. Even if a victim lost 200k on such a scam, it’s obviously hard to justify spending 50k with no guarantee of recovering anything.

The way we see it, there are 3 types of entities here that could potentially be appropriate to take civil action against:

Exchanges and/or OTCs

In most cases, the [exchange] accounts that funds eventually go to that are associated with major exchanges are most of the time not controlled by the perpetrators themselves, but more often belong to or are associated with entities the scammers did business with (this is not factoring in victim accounts of course, because as mentioned, it’s not uncommon to see much smaller payouts to victims as part of the confidence ploy).

More often, the exchange accounts belong to OTCs or P2Ps the scammers have conducted trades with, although there are certainly exceptions. This begs the first question, could the OTCs or P2Ps be held liable? We can’t and won’t offer any legal opinion in this regard, but it would be fair to say that there may be challenges with this approach.

First, because it can take some time or could be challenging to identify the applicable party, second because that party may be in a less than ideal jurisdiction that may be difficult to pursue in, and third because the OTC/P2P may have only received a portion of the funds, rather than everything. Obviously, there are other pertinent questions as well, such as if the OTC/P2P was operating perfectly legally in their jurisdiction or not (what is illegal in one jurisdiction may be perfectly legal in another), and what compliance policies and procedures they utilized (if any).

In terms of trying to hold exchanges accountable for receiving illicit funds and/or not having adequate compliance policies to ensure OTCs that did business on their exchange were also acting in a compliant manner, this has its own challenges. Apart from the obvious legal questions of whether the exchange could be held liable or responsible even if true, and if so to what extent, there are a variety of other issues.

For one, it’s common to see less-than-compliant exchanges employ ‘jurisdictional gymnastics,’ whereby they pick out a more favourable jurisdiction for registration, but often have a plethora of affiliated entities with an unclear corporate structure. For example, Kucoin, OKX, and Huobi are all officially registered in Seychelles.

As you can no doubt guess, their reason for choosing Seychelles is not because they all have a bunch of people that actually work in Seychelles. Any prospective victim trying to go the exchange lawsuit route should be well aware that it could be expensive against a well-funded entity that has been structured in a way so as to limit legal liability and make it challenging to pursue, and it could well have jurisdictional challenges anyway, with no guarantee of the victim seeing any money back.

Tokenlon

For reasons we previously described, the most favourable description that Tokenlon could be considered would be akin to a centralized OTC desk masquerading as a decentralized exchange. In many cases, however, it’s worse than that, with Tokenlon knowingly taking custody of illicit funds, performing the transaction requested but their customer, and paying their customer out immediately accordingly, all without any consideration or thought of compliance or anti-money laundering regulations.

Tokenlon is officially based in Singapore, but it too has some connections to China. Singapore might be a more practical decision to pursue such a case in but we don’t know of any case like this that has been tested in any court in the world and we aren’t sure what the legit merits of what such a case would be either.

Liquidity Providers

We’ve never heard of a case (yet) whereby liquidity providers that provided large amounts of liquidity to a DEX ever faced repercussions for facilitating illicit transactions. We also aren’t sure what type of merits such a case would have. Suffice to say, it is a curious one to ponder. If a select few entities engaged in a scheme whereby they provided the vast majority of liquidity to a ‘DEX’ which had a very large portion of illicit activity, and whereby such liquidity providers knew or ought to have known of this, could the liquidity providers themselves be held liable? These liquidity providers are often investment funds of various types, but their jurisdictions can vary more widely.