What is an NFT?

A Non-fungible Token (NFT) is a unique digital asset and piece of data stored on a blockchain. The NFT is a unique token recorded as belonging to a given wallet, and it is not indistinguishable or interchangeable amongst other tokens of the same type. For example, the NFT representing Cryptokitty x, is distinguishable from the NFT representing Cryptokitty y, which are also not necessarily of equal value either.

If an individual controls the given wallet, they can be said to ‘own’ the NFT. This does not necessarily mean that the digital media of whatever the NFT represents cannot be duplicated. However, we first need to understand current applications of NFTs as how NFTs are utilized can vary considerably from one application to another.

NFT Applications

Below are a few examples of what are currently the most commonly used applications for NFTs.

Digital Art

A common application for NFTs is digital art. Some digital art NFTs have sold for some truly staggering prices, such as an NFT from the artist ‘Beeple’ that sold for $69 Million USD.

To illustrate what exactly the NFT is here, we’ll use the example of Beeple’s art piece, “Everydays: The First 5000 days.” Details were posted by Christie’s auction house.

Some people think that the art itself is stored on the Ethereum blockchain, but this isn’t technically true. Rather, the art is represented as NFT, and the NFT is what’s stored on the blockchain. We recognize this is a confusing concept, so let’s dig into this more with an example.

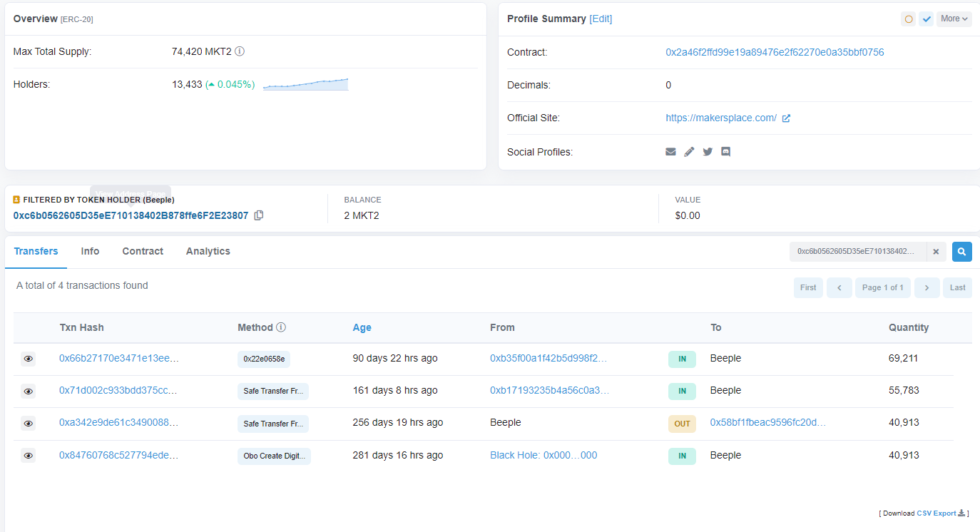

As noted by Christie’s auction house, Beeple’s wallet is 0xc6b0562605D35eE710138402B878ffe6F2E23807, the smart contract is 0x2a46f2ffd99e19a89476e2f62270e0a35bbf0756, and the ‘Token ID’ is 40913.

The NFT was minted on February 16, 2021, UTC, using MakersPlace (and more specifically the Makersplace contract 0x2a46f2ffd99e19a89476e2f62270e0a35bbf0756) in transaction 0x84760768c527794ede901f97973385bfc1bf2e297f7ed16f523f75412ae772b3. The unique token ID (on the Makersplace contract) is 40913.

The digital media itself is not hosted on the Ethereum blockchain. As shown in the logs, the NFT token references an IPFS (Interplanetary File System) hash.

The metadata links to an IPFS gateway run by Makersplace. As Twitter user @Jonty notes, at some point in the future, Makersplace will no longer exist, and thus the data will only exist on IPFS if it’s hosted by an IPFS node willing to host it.

While this is certainly more decentralized and censorship-resistant than the traditional web, it does not mean the art will continue to be hosted on IPFS. Regardless, IPFS is not a blockchain, and the art itself cannot be said to be hosted on any blockchain. Rather, a token exists on the Ethereum blockchain representing the art. It’s important to note the distinction between the NFT versus the art itself. And while this Beeple art piece is hosted on IPFS, many pieces of art are hosted or stored in a far more centralized manner.

Collectibles

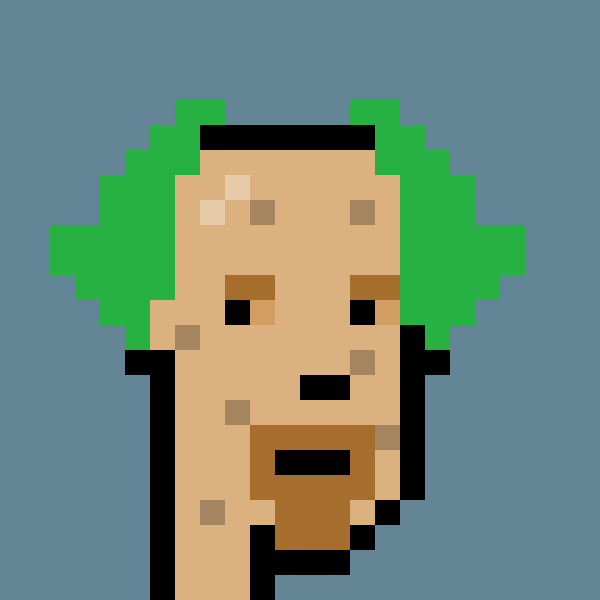

Digital collectibles are one of the most common applications of NFTs. Some of the most well-known collectibles include Cryptokitties and Cryptopunks.

Just like with digital art, the digital media behind a given Cryptokitty is not stored on the blockchain. It’s stored on a server belonging to Cryptokitties. However, Dapper Labs has noted they are working to store on IPFS in the future. However, there is a unique token ID for each Cryptokitty NFT per the Cryptokitties Ethereum contract 0x06012c8cf97bead5deae237070f9587f8e7a266d, and the token is stored on the blockchain, and applicable tokens are located ‘in’ wallets.

The implications of this so far as fraud and money laundering are concerned will be discussed later in this article.

Gaming

Gaming NFTs tend to have a fair bit of overlap with collectible NFTs. These NFTs simply tend to allow people to do more with their digital assets than what one would typically be able to just do with a collectible. Namely, you can play games with digital assets, of which NFTs that you own will typically represent. One of the most popular games that utilize NFTs right now is Axie Infinity.

This is quite a bit more than you’d be able to do with a Cryptokitty. The main functional thing you can do with a Cryptokitty, once you own it, is the ability to breeding it, as well as sell it. This isn’t to suggest that there aren’t other reasons for owning a Cryptokitty (intrinsic reasons, or having a desire to post a picture of a Cryptokitty you can rightfully say you own as your Twitter profile picture, or just because it’s fun for example).

Just like with digital art and collectibles though, the digital media behind Gaming NFTs is not stored on the blockchain. NFTs are only the tokens that make reference to them. Usually, the digital media is usually hosted on a server belonging to the game maker. The idea of course is that if you transfer the NFT to someone else, the digital media content transfers as well.

The primary functionality of the NFT is for use in the given game. However, note that it would theoretically be possible for a third party to make use of the NFTs are part of a different game not run by the game maker. The third-party could build ‘Axie Infinity Improved’ and credit users with corresponding Axie Infinity NFTs with in-game assets. Does this happen in practice? To the best of our knowledge, no, as it would likely result in a lawsuit from the company behind Axie Infinity to whoever designed ‘Axie Infinity Improved.’

Domains

One of the most interesting applications for NFTs is for the use of domain names, but not through the traditional DNS that most of us are used to, which is managed by ICANN.

More specifically, we’re referring to blockchain-based domains utilized the Ethereum Name Service (ENS), Unstoppable Domains, or Handshake Protocol which act as an alternative to root DNS managed by ICANN.

ENS domains are NFTs and those tokens give their owner access to a namespace that adheres to the ENS protocol.

Virtual Real Estate

Virtual real estate is another application for NFTs. Just a few days ago, a plot of land on Decentraland sold for $2.4 million, a virtual reality platform.

Real World assets

NFTs are mainly used in the digital world, but that doesn’t mean there can’t be crossover with the physical world. An NFT could be used to represent property ownership, or even fractional property ownership, much like the title to a home.

NFTs could also conceivably be used as licenses, rights or certifications of various sorts, or intellectual property.

Currently, there aren’t many real-world applications actually being utilized, but that may be largely due to legal challenges and/or incompatibility with existing methodologies and procedures that are used to hold and transfer such assets.

Using NFTs to Launder Illicit Funds

Imagine a situation where an individual has acquired fungible cryptocurrency assets through illicit means, e.g., a hack, scam, or ransomware. Are such funds being laundered by purchasing NFTs, and then potentially reselling the NFTs back later as a way of subverting the traceability of the funds?

The short answer is no. It doesn’t make sense to do so because NFTs are trackable, just as fungible cryptocurrency assets are. If stolen ETH is subsequently used to purchase an NFT, we could still track what the wallet owner elects to do with the NFT after. In most cases, it wouldn’t make any sense to continue tracking the ETH that was sent to pay for the NFT.

Thus, NFTs don’t work well to obfuscate the trackability funds that have already been acquired through illicit means. Additionally, when an individual is trying to launder funds, they generally want to have a more liquid asset that can easily be used to pay for goods or services. An NFT, by definition, doesn’t offer that, so using NFTs to launder these types of funds would be counter-intuitive in most cases.

That being said, at Cryptoforensic Investigators we have encountered situations whereby stolen funds, that thieves thought they had safely laundered, were then used to purchase NFTs. But the distinction here is that when those purchases were made, we have no reason to believe such NFTs were purchased with the intent to launder money (since we believe they thought it was already safely laundered), and it would thus be more akin to the purchase of a good or service, just as any other good or service could be purchased with illicit funds.

This is not to suggest the other way around doesn’t happen, though. NFTs can and do get stolen, and the first thing we normally see when this happens is the hacker liquidating the NFT for ETH as fast as possible, which is a fungible asset. But in this regard, the NFTs aren’t being ‘used’ for money laundering, since they are merely being liquidated (if anything, it could be said that ETH is being ‘used’ for money laundering in this scenario).

Money Laundering and NFTs

Can NFTs be used to effectively launder money? In some situations, yes, they absolutely can be. And this shouldn’t be that surprising given that there are some seemingly eye-popping sales of certain NFTs that almost any sane person wouldn’t be able to justify spending the gas on even if the NFT was free! Take the absurd sale of an NFT ‘rock’ for $1.7 million USD as but one of many examples. Imagine the following hypothetical scenario:

- Party A wants to sell illicit goods (drugs, munitions, or whatever) to Party B

- Party A either creates an NFT on their own or buys an existing NFT with ‘clean’ money.

- Party A and Party B secretly agree that Party B will purchase the NFT from Party for $1.7 million, which will, of course, come with the illicit goods, but there won’t be any way to identify that an additional exchange (beyond the NFT) was performed here, beyond the $1.7 million being traded for a JPEG of a rock. It will look like Party B simply decided to purchase the NFT for a ludicrous price.

- Party B ‘purchases’ the NFT in exchange for $1.7 million.

- Party A receives the $1.7 million and gives the appearance that they earned this through their ‘creative’ efforts or hard work.

The only real question that needs to be asked here is why bother including the NFT aspect at all if both parties are complicit in the illicit transaction? Why doesn’t Party B just transfer the $1.7M to party A in exchange for the illicit goods and let that be the end of it?

The answer is the ability to justify this transaction to a third party, such as the IRS for example, to show the source of income that was earned. The scheme noted above provides plausible deniability and a plausible ‘story’ that cannot be ruled out, at least not without deeper investigation.

NFTs and Tax Evasion

Justifying illicit transactions as part of a ‘business’ transaction with another party and subsequently trying to justify that to a tax agency is but one practical example of how NFTs could conceivably be used to launder money. But there are more.

We discussed earlier why it wouldn’t make sense to convert illicit funds to an NFT if the desire was to not have it trackable or linked to the incident. But imagine another hypothetical scenario.

- A hacker that stole funds from hundreds of people wants to ‘realize’ or ‘cash out’ his ill-gotten money.

- The hacker may or may not have undertaken an attempt to ‘clean’ the money prior to doing so.

- The hacker creates an NFT or buys an existing NFT with clean money.

- The hacker utilizes the illicit funds to purchase the same NFT he already owns. The liquid assets are then in his new wallet — the same wallet he used to initially create/acquire the NFT.

- The hacker now has the appearance that he has ‘earned’ his money through legitimate work.

- The hacker proceeds to send the funds to an exchange or otherwise find a means of getting them to his bank account.

- The hacker then can even decide to report this as income on his tax return (if he wants to). And if inquired about the source of funds, he can claim he was from the NFT sale, which offers him plausible deniability at the very least.

Thus, NFTs do have practical applications with regard to money laundering. The harder part to assess is just how common this type of laundering is.

Overlooked Legitimate Uses of NFTs

There are some legitimate reasons why NFTs might sell for eye-popping valuations.

First, it could be for intrinsic reasons or to be part of an exclusive club. Cryptopunks is a prime example of this. Many people have gotten rich by investing in cryptocurrency, and some people simply have more money than they know what to do with. There are only a select number of Cryptopunks, so there’s a degree of rarity to them, and the nature of how Cryptopunks came to be, and its limited supply, gives Cryptopunks value to some people, even if the actual images of Cryptopunks make one wonder if the buyer is of questionable mental capacity.

Second, it could be used to fund a cause, much like a donation. Imagine a situation where a famous sports star signs a physical jersey of theirs and auctions it off for charity or for an otherwise good cause. An NFT could arguably serve a very similar purpose. The NFT could be created and auctioned by the sports star, and the fact that they created something special and unique gives it value, as might be the cause that it was created for.

NFT Scams and Frauds

Just like with other cryptocurrency assets (and non-cryptocurrency assets), NFTs can be utilized or otherwise play a role in various types of frauds and scams, apart from the obvious where if your wallet is compromised, your NFTs will likely be stolen, and subsequently liquidated, perhaps at a ‘below-market rate’ if the hacker is trying to do so quickly. There are a variety of other ways that NFTs are used as part of scams.

NFT Price Manipulation

How exactly can one fairly value what an NFT is worth? After all, it’s non-fungible, right? A sizable portion of NFT investors choose to invest in NFTs in the hope that it’ll be worth more in the future. So how can they assess what the value of a prospective NFT they’re considering buying might be worth?

One idea they might utilize is to look at what the NFT sold for in the past, which they could uncover via past on-chain activity. Scammers know this and use it to their advantage. Taking the ‘Rock NFT’ example again, the scammer could simply purchase the NFT from themself at whatever price they want — the scammer wouldn’t lose any money apart from transaction fees.

Thus it would give the prospective buyer an illusion of value since the NFT sold for a seemingly high price before. Thus the buyer might be able to resell it for even more in the future. Maybe the buyer will even think it’s getting a ‘fantastic deal’ on the NFT by purchasing it at what they believe may be ‘below market value.’

Of course, what ends up happening is that the buyer can’t sell the NFT for even a small fraction of what they paid for it.

However, this action performed by the NFT seller or ‘NFT Price manipulator’ probably wouldn’t constitute money laundering and arguably may not even be illegal in most jurisdictions — there’s nothing wrong with someone purchasing their own NFT, right?

NFT Duplicates and Fakes

The digital media behind many NFTs can be copied. Just because someone has posted a Cryptopunk NFT image as their Twitter profile image doesn’t necessarily mean they own that image. There’s nothing that stops someone from copying that NFT image, creating an NFT token that purports to be original and authentic, and selling it under the guise of it being authentic when it’s not.

The actual token itself cannot be duplicated. It has a unique token ID associated with a specific smart contract.

The issue is that people don’t always do adequate due diligence when trying to verify the authenticity of an NFT token to see if it’s a duplicate or fake. Some NFT marketplaces do some due diligence themselves to those wanting to list an NFT for sale on the marketplace. A prime example of a fairly fake NFT is the fake $300k Banksy NFT.

Ultimately there are a variety of different possible ways scammers try to create fake NFTs. With Art NFTs, it’s important to understand what gives them value. In the case of the Banksy NFT, if that exact same art had been produced by another artist far less notable than Banksy, it’s unlikely it would have fetched even a fraction of the $300k. A significant part of that would give it value is if Banksy, a well-known and popular artist, created both the art as well as the NFT that represents the art. Thus a critical question in such a situation is whether or not the (real) Banksy create the art?

This should not be surprising. Known duplicates of high-value pieces of art are valued at only a minuscule fraction of the real thing due to lack of authenticity, and thus authenticity and provenance of an NFT in this situation is perhaps the most important element that one needs to do their due diligence on.

Furthermore, consider another hypothetical scenario. A celebrity’s Twitter account is hacked, and then the account suddenly posts an NFT for sale that they purportedly created themselves. Maybe they even say proceeds of the sale will be donated to charity. But of course, it’s the scammer saying these things through the celebrity’s Twitter account. Authenticity and provenance are of paramount importance.

NFT Projects that are Scams

There are NFT projects out there that are scams, or that could arguably be described as scams. In some cases, the “project” doesn’t exist at all, just like fake cryptocurrency trading platforms, which of course, pretend to have a platform that people ‘trade’ on.

In other cases, it’s not quite as obvious that it’s a scam, and the NFT projects may operate in a highly centralized manner, where there is little or more often no practical use case for the NFTs. If this is eerily reminiscent of the 2017 ICO boom to you (which has seen a resurgence), that’s because it is.

There are also real ‘NFT projects’ where there are no actual NFTs involved!

A Comparison to ICOs

Many NFTs are highly speculative, and investors see some eye-popping returns on them. Thus, projects that incorporate the use of NFTs are able to solicit more money than they would otherwise be able to if there were no NFTs. Thus integrating the use of “NFTs” makes it easier to raise more funding more easily from prospective investors.

This also incentivizes projects to find a way to integrate NFTs into their project. They will find an excuse to build in “utility” for the NFT. We’ve seen non-NFT projects that suddenly decided to change course and integrate NFTs in their project since that’s where the money is (or that’s how they thought they could raise more money). In reality, the NFTs are really unnecessary or have very minimal practical use, and what “utility” they have is largely contrived by the project. In layman’s terms, many would reasonably describe this as a “cash grab.” Granted, a “cash grab” isn’t inherently illegal. Misappropriation, negligence, or fraudulent misrepresentation might be though.

Overall, it’s a bull market for NFTs right now, but in our opinion, interest in speculative NFTs solely for investment purposes will die down sooner or later.

Many of the NFT projects that exist today exhibit very similar characteristics to projects that have launched token sales, and indeed a good portion of NFT projects also have their “own native [fungible] token” as well also for largely contrived reasons to solicit more money, even though on the surface it’s utility might be supposedly for “governance” of the platform/protocol.

Summary

NFTs can be utilized to launder money as fraudulent NFT transactions may offer plausible deniability, thus leading to tax evasion. Additionally, NFTs are used in a variety of other types of scams and frauds, are manipulated in various ways by scammers, or in some cases projects or companies trying to make a quick buck on a highly speculative asset class.

Note: Nothing in this article is to be construed as legal advice